Friends,

Last week I took a vacation. Actually, these being the days of COVID, it was technically a “staycation” because I spent every night in my own bed, but on one of my staycation days I took a long drive to Lake County and back. It was a mini pilgrimage to Bo-No-Po-Ti, an island in Clear Lake that most folks today call “Bloody Island” because it was the sight of what may have been the deadliest single-day attack by the United States Military against native people. Ever.

I say it “may have been” the deadliest attack because no one really knows for sure how many people were massacred that day. The army’s official count was sixty people—all members of the Pomo nation—but most credible estimates by legitimate historians put the death toll much higher—anywhere from one hundred to eight-hundred Pomo people (by contrast, the US military killed 250 people at Wounded Knee). Regardless of the number of people killed, Lt. Nathaniel Lyon, commander of the 1st Dragoons of the US Cavalry described the massacre he oversaw on Bo-No-Po-Ti as “the perfect slaughter pen.” (Lt. Lyon, who has a street in San Francisco named after him, eventually achieved the rank of general and is remembered with fondness as a patriot and hero for his distinction of being the first Union general to die in combat during the Civil War.)

Emotionally and spiritually, there is a lot to unpack from my pilgrimage to Bo-No-Po-Ti, and I’m going to preach about my experience in Lake County on Sunday (so please be sure to come to celebration to hear more), but what I cannot do from the pulpit is show you photos I took on the trip. These photos are not necessarily artistic, but I was interested in taking note of how signage on historical markers interprets what happened at Bo-no-Po-Ti on May 15, 1850, and why.

The first sign I found was actually several miles from Bo-No-Po-Ti, at the place where a band of Pomo insurrectionists killed Andrew Kelsey and Charles Stone, two of the first white Americans to settle in what we now call Lake County. Kelsey and Stone enslaved Pomo and other local indigenous people, and by all reports they were cruel and sadistic. They abused, raped, and murdered the people they enslaved and in response to Kelsey and Stone’s brutality, an enslaved woman poured water down the barrels of Kelsey and Stone’s rifles, rendering them useless when Pomo warriors attacked and killed the two slave holders. That story is more or less told on this sign which is just outside a small town called—ahem—“Kelseyville.” What is not told here is that a few months later, the US Army attacked and killed hundreds of Pomo people—most of them women and children—at Bo-No-Po-Ti. No one knows if any of the dead had anything to with the Slave insurrection in what we now call Kelseyville. Probably not.

After visiting Kelseyville I drove out to Bo-No-Po-Ti. Around the turn of the 20th Century, the US Bureau of Reclamation drained the northwest part of Clear Lake in an effort to make farm land. As a result, Bo-No-Pot-Ti is now a hill.

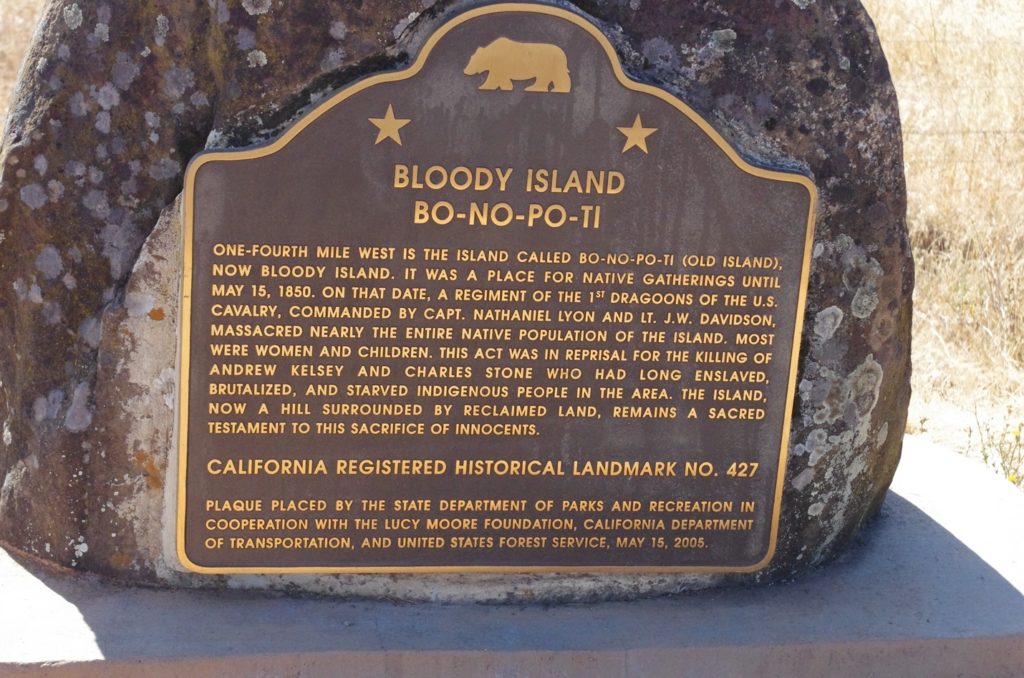

In 2005, on 155th anniversary of the massacre, a new historical marker was erected on Highway 20, about a quarter of a mile from Bo-No-Po-Ti, at the place where I took the photo above. This sign does a good job of providing a brief description of what happened on Bloody Island. It is interesting to note that that marker was placed with the cooperation of the Lucy Moore Foundation. Lucy Moore was a child on Bo-No-Pa-Ti and was one of the few people to survive the massacre. She lived to be 110 years old and would go on to become one of the most celebrated and accomplished Pomo basket weavers.

The sign on Highway 20 stands in stark contrast to a smaller historical marker that sits on the base of Bo-No-Po-Ti, down a rutted country road. This sign is incorrect in several ways: it calls the massacre a “battle,” it provides the wrong date, it misspells the name “Lyon” (misspelling last names with the addition of a final “s” is a mistake to which I am particularly sensitive), it says the Pomo people fought under the command of Chief Augustine who was one of the insurrectionists in Kelseyville, but no one knows if he was even on Bloody Island on the day of the massacre. Also, the sign was placed by the “Native Sons of the Golden West,” an organization that sounds like it is comprised primarily of Native Californians; it is not.

But take a step back and notice that modern Pomo people have transformed the woefully erroneous marker into a shrine, something sacred and, for me anyway, deeply moving. I suppose there’s a great deal of spiritual truth in the transformation. It’s a good reminder: whether by draining a lake or providing incorrect or misleading signage, when an attempt is made to erase or sanitize history (or turn an island into a hill), that act of historical vandalism does not need to be the final word. If we learn, and remember what we’ve learned, memory can go on and perhaps, in the words of the psalmist, “Steadfast Love and Faithfulness will meet; righteousness and peace will kiss.” (Psalm 85:10)

God’s Peace,

Ben Daniel (no final “s”)