In last Sunday’s sermon I “outed” myself as a mystic. Clearly not a FAMOUS mystic, but I do have mystical tendencies, value the teachings of Christian mystics (in particular) and I have embraced a number of spiritual practices that are often labeled “good for mystics”.

In last Sunday’s sermon I “outed” myself as a mystic. Clearly not a FAMOUS mystic, but I do have mystical tendencies, value the teachings of Christian mystics (in particular) and I have embraced a number of spiritual practices that are often labeled “good for mystics”.

My journey with mysticism began when I was introduced to the great medieval Christian mystic Hildegard von Bingen. Hildegard’s life and writing, in particular, resonate with me because I also love her beautiful music. Singing, chanting, and playing music from a place of spiritual contemplation is still my most beloved (and effective!) spiritual practice. Long before I knew anything about mysticism, I had already discovered that playing the piano was a way that I could experience the divine in an immediate and powerful way. In the throes of adolescence when I knew I was “different” or when things weren’t going well, the piano was my refuge.

In seminary, my spiritual director first challenged me to consider a silent retreat. This was no surprise since spiritual directors are pretty much honor bound to suggest these things. In addition, I’m pretty sure he thought that this might be a way to tame some of my extreme extroversion, too. Still, his invitation wasn’t really the thing that finally got me to go to a convent and to later crave silence and contemplative spiritual practice.

Sometime, somewhere in the early 90’s, I heard an interview with Nelson Mandela that changed my thinking completely about the importance of silence and contemplation. The interviewer asked Mandela how it was that he came to embrace forgiveness and reconciliation after all that had been done to him by the apartheid regimes. Mandela spoke of what it was like to spend so many years alone and in silence while he was in prison. He then told the interviewer that once he truly had seen his own soul in this way, he knew something about his own failings and need for forgiveness. And in the silence, trying to face up to his own failures and need for forgiveness, he became committed to the path of forgiveness and reconciliation for all peoples. The rest of that story, of course, is history that we are now remembering upon the occasion of Mandela’s death.

So without being arrested and hauled off to prison, I decided to follow Mandela’s spiritual path by voluntarily committing myself to at least a few days in a monastic cell. My first silent retreat was really hard. I chose to go to a Franciscan convent in the Santa Cruz mountains near Soquel, California called St. Clare’s Retreat. While I was on a personal retreat, there was a large group from a Hispanic Roman Catholic parish in San Jose there at the same time. The young priest from Mexico who was leading their retreat spoke little English and so mealtimes were a multi-layered, multi-cultural experience for me. But the real difficulty came when I sat in my “cell” and was forced to listen to my own mind for hours on end.

So without being arrested and hauled off to prison, I decided to follow Mandela’s spiritual path by voluntarily committing myself to at least a few days in a monastic cell. My first silent retreat was really hard. I chose to go to a Franciscan convent in the Santa Cruz mountains near Soquel, California called St. Clare’s Retreat. While I was on a personal retreat, there was a large group from a Hispanic Roman Catholic parish in San Jose there at the same time. The young priest from Mexico who was leading their retreat spoke little English and so mealtimes were a multi-layered, multi-cultural experience for me. But the real difficulty came when I sat in my “cell” and was forced to listen to my own mind for hours on end.

In the stillness, I watched my own fears and insecurities rise up like demons. Every error, every mistake I had ever made haunted my every moment-by-moment decision-making about whether to read, walk around, or try to work on a sermon on Yael for my preaching class. The choice to bring Yael as a companion on a silent retreat was particularly bad. (and it didn’t produce one of my best sermons either)

During this first retreat, I discovered why so many monasteries have structured prayer times. It is very difficult to constantly choose for yourself how to spend your time in solitude. The bells that called us all to the chapel for prayer were a relief from having to confront your own inner craziness. This insight alone was life-changing for me. Feeling stressed, lonely, or sad? Lean on a structure that feeds your spirit. Plan times for meditation, walking, exercise, music practice and you’ll be less crazy. And there are so many potential spiritual practices – just about anything that you do in some regular way at a regular time can be of great comfort in times of distress.

Since that first retreat over twenty years ago, I have made time for silent retreat as often as possible and two years ago, I finally found the monastery that provides the perfect mix of spiritual practices for me.

Since that first retreat over twenty years ago, I have made time for silent retreat as often as possible and two years ago, I finally found the monastery that provides the perfect mix of spiritual practices for me.

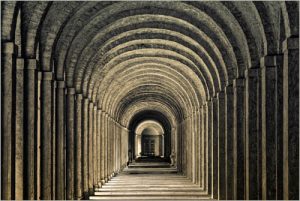

Christ in the Desert is located about 45 minutes off the highway past Ghost Ranch in Northern New Mexico. The landscape alone brings me to awe. The community of monks follows a form of primitive Benedictine practice. They begin at 4:00 a.m. with the office of Vigils and they then pray the full monastic office. In each of these offices, the monks chant the psalms, and if you go for a full week, you can chant all 150 psalms. The singing is acappella and based upon ancient psalm tones that are notated in such a way that significant training in music (or monasticism) is required in order to participate. Most folks simply listen to the monks, but I enjoy that my early music professor Dr. Anne Schnoebelen at Rice taught us to read this notation so I get to sing all day!

Chanting the psalms is another window into the breadth and depth of the human soul. While there are beautiful words of praise and thanksgiving, many psalms have large sections of violent pleadings for revenge asking God to “smite” the psalmist’s enemies. It is humbling to sing these texts and “put these words in your own mouth” because – in the silence – you come to understand that some part of your soul prays this way all the time. But just as you recognize your own internal violence, another psalm will call you to repentance and new life, and then back to praise and thanksgiving.

While contemplative spirituality does not appeal to everyone, it certainly is unfair to label such practices as “navel-gazing” or “self-serving”. In my own experience, these practices have been instrumental in helping me become more compassionate and forgiving of myself and of others.

And so today I will light a candle, chant the psalms, and give thanks for the life of Nelson Mandela who learned to change the world by first starting with his own soul. In silence.